I won't forget in a hurry the sound of Manal Bahie al-Din's voice just after she heard the decision to free her husband, blogger and political activist Alaa Seif al-Islam. Alaa has been held at the State Security Prosecutor's pleasure since May 7, on the Kafka-esque charges of insulting the President, obstructing traffic and endangering public order. Manal's voice was pure joy, flowing uncontrollably after six weeks of being separated from her husband.

Part of the reason I shan't forget this is that I was able to hear it in the first place. Alaa, his mother Layla Soueif, his father Ahmad Seif, his wife Manal are all charming, accessible and, of course, fluent in English. Their story, over the past six weeks, has made it around the world, into newspapers, magazines and websites. They are a highly internationalised face of the Egyptian pro-reform movement - and in the eyes of the western media, a much more saleable story than the countless cases of Muslim Brotherhood activists carried away from their families in the night. Only the heaviest of crackdowns directed at Brotherhood members ever make it to any but the most dedicated foreign outlets. But this should not surprise us. The Brotherhood have always presented a very distinct 'other' that external diplomats and journalists find difficult to penetrate, and a great many do not try.

So now, we have a new situation. Alaa has become something of an international figure. He may or may not be comfortable with it. I do not know him personally, but knowing that he only recently left the comfort of cyberspace for the hot brutality of downtown demonstrations, I suspect that he will not. But regardless of whether or not he is ready to take it, the mantle of web-hero for the Egyptian reform movement (and identifiably westernised hero for the foreign media) is already being lowered onto him. In short, within six weeks he has become the perfect 'prisoner of opinion'.

Now, we don't necessarily know what those opinions are. We can make a fairly safe bet that they are at root anti-authoritarian. We know for a fact that they form a strong dislike for the government of Hosni Mubarak, Ahmad Nazif, et al. But aside from that, it's all a bit vague – or at least, it is reported as such because the restrictions of conventional media will reduce this and any other story to an essentially heroes and villains piece. In this case, that's probably accurate enough.

But regardless of what Alaa - or Youth for Change, or Kifaya, or Artists and Writers for Change or whatever – actually stand for, here we have a hero. The fact that he is a blogger - an identity boosted to popular comprehension by the likes of Salam Pax in Baghdad - is perfect. It's the ultimate representation of intellectual freedom (i.e. the internet) versus the ultimate representation of morally bankrupt, intellectually perverted semi-competent bureaucracy - The Egyptian government.

So, here is a real opportunity. An opportunity to use the political capital that six weeks in prison brings. An opportunity to use an education and a global perspective that so many who have tried to take on the Egyptian state have not had. An opportunity to lay bare the abuses and brutality of the security state. An opportunity to succinctly publicise the corruption and perfidy that is the so-called process of 'economic reform' - where imported neo-liberal ideologies are lining the pockets of the privileged few. An opportunity to tell the world from a first hand perspective what it is like to be a 'prisoner of opinion' in this country. And an opportunity to prove that the secular opposition in Egypt has more to offer than banners on the steps of syndicates and tales of cameraderie from the insides of dirty jails.

I look forward to his first, post-prison, blog.

Thursday, June 22, 2006

Sunday, June 18, 2006

Fire-Eaters

Last night, I happened to be sitting at the qahwa in Nabrawy street, behind the Champollion palace, when, like an apparation from another age, a fire-eater appeared from no-where and began his show. The gentlemen at the cafe seemed less than interested, never mind impressed, at this unusual entrant.

The man intoned a bismillah, drank the paraffin, and began breathing plumes of fire and smoke along the length of the street, perilously close to the ancient trees that rest against the wall of the palace. He extinguished a number of burning torches in his mouth with little ceremony, and began a short spiel about how, really, fire was not for eating, and paraffin was not for drinking and that we should be mindful of our Gods, whatever they might be. He collected a few piastres donated by the customers, and promptly left. I didn't have my camera, much to my shame, so there are no photographs. But, to be honest, I'm not altogether convinced he was real, so short and ethereal was his visit.

My companion watched the brief performance with narrowed eyes, and afterwards pointed out that the appearance of such a character was, in itself, socially significant. The presence of roaming performers, marabouts, shamens, street magicians, and indeed fire-eaters indicates a wider malaise in the land, it seems. And hardly anything, if one looks at it reasonably, would suggest hardship more obviously than a man swallowing paraffin for a living.

The fire-eater, whatever his name was, was some kind of living anecdotal evidence about what is happening in this country that is almost impossible to grasp. It's not impossible to grasp because it is conceptually difficult – poverty is never that. It is difficult to grasp because the dominant discourse in this nation does not allow 'it' to exist. And by 'it' I mean deepening, widening poverty, the kind which makes those who live on five pounds a day (50p) feel fortunate because they are not one of those living on two. It doesn't exist because those who live like that are becoming, statistically, unwelcome. Every major aid NGO paints a picture of growth and progress, sometimes only moderate, sometimes mitigated, but progress nonetheless. Linear, empirical growth towards that happy place known as development. And as for the state, forget about it. So for anyone trying to tell a story which they so often, anecodotally, hear – that the poor are becoming, quite literally, immeasurably poorer –it's no use looking for reports and facts and figures to back up the hunch. There aren't any.

Every week someone tells me that Egypt is reaching boiling point, that the poor can't take any more, that it is ripe for revolution. And every week at least five people tell me that Egypt is going places, that it is a confident, able, 'emerging market' (That phrase has always made my flesh crawl. 'Emerging' from what, 'Emerging' for whom?) that will be a regional and world player this century. Well, they're probably right. The statistics are there to back them up. I have a pile of them on my desk. They make dizzying reading: Real GDP Growth Rate, 2005, 5.1%. Investments as % of GDP, 2005, 17.2%. Net International Reserves, 2005 US$ 19.3 bn. Net Foreign Direct Investments, 2005 US$3.9 bn. Looking good. There's no shortage of this stuff.

Start asking different questions, the stats dry up. How many people living on under $2 a day? We don't really know. Maybe 40%. How many people living in informal housing in Cairo? We don't know. How many people in Cairo not eating a minimally nutritious diet? We don't know. True, these kind of things are a lot harder to measure than the value of exports per quarter. And they are also harder to fix than to turn around a trade deficit. The question is whether or not, with the trumpeted quarterly growth figures, and the lauded economic reform, and the crowed-about FDI numbers, the condition of those way, way below the 'poverty line' are seeing any improvement whatsover. The anecdotal evidence is that they are not. The anecdotal evidence says that they are resorting to strategies that damage the body and demean the spirit. They are drinking petrol and breathing fire in alleyways to stay alive.

The man intoned a bismillah, drank the paraffin, and began breathing plumes of fire and smoke along the length of the street, perilously close to the ancient trees that rest against the wall of the palace. He extinguished a number of burning torches in his mouth with little ceremony, and began a short spiel about how, really, fire was not for eating, and paraffin was not for drinking and that we should be mindful of our Gods, whatever they might be. He collected a few piastres donated by the customers, and promptly left. I didn't have my camera, much to my shame, so there are no photographs. But, to be honest, I'm not altogether convinced he was real, so short and ethereal was his visit.

My companion watched the brief performance with narrowed eyes, and afterwards pointed out that the appearance of such a character was, in itself, socially significant. The presence of roaming performers, marabouts, shamens, street magicians, and indeed fire-eaters indicates a wider malaise in the land, it seems. And hardly anything, if one looks at it reasonably, would suggest hardship more obviously than a man swallowing paraffin for a living.

The fire-eater, whatever his name was, was some kind of living anecdotal evidence about what is happening in this country that is almost impossible to grasp. It's not impossible to grasp because it is conceptually difficult – poverty is never that. It is difficult to grasp because the dominant discourse in this nation does not allow 'it' to exist. And by 'it' I mean deepening, widening poverty, the kind which makes those who live on five pounds a day (50p) feel fortunate because they are not one of those living on two. It doesn't exist because those who live like that are becoming, statistically, unwelcome. Every major aid NGO paints a picture of growth and progress, sometimes only moderate, sometimes mitigated, but progress nonetheless. Linear, empirical growth towards that happy place known as development. And as for the state, forget about it. So for anyone trying to tell a story which they so often, anecodotally, hear – that the poor are becoming, quite literally, immeasurably poorer –it's no use looking for reports and facts and figures to back up the hunch. There aren't any.

Every week someone tells me that Egypt is reaching boiling point, that the poor can't take any more, that it is ripe for revolution. And every week at least five people tell me that Egypt is going places, that it is a confident, able, 'emerging market' (That phrase has always made my flesh crawl. 'Emerging' from what, 'Emerging' for whom?) that will be a regional and world player this century. Well, they're probably right. The statistics are there to back them up. I have a pile of them on my desk. They make dizzying reading: Real GDP Growth Rate, 2005, 5.1%. Investments as % of GDP, 2005, 17.2%. Net International Reserves, 2005 US$ 19.3 bn. Net Foreign Direct Investments, 2005 US$3.9 bn. Looking good. There's no shortage of this stuff.

Start asking different questions, the stats dry up. How many people living on under $2 a day? We don't really know. Maybe 40%. How many people living in informal housing in Cairo? We don't know. How many people in Cairo not eating a minimally nutritious diet? We don't know. True, these kind of things are a lot harder to measure than the value of exports per quarter. And they are also harder to fix than to turn around a trade deficit. The question is whether or not, with the trumpeted quarterly growth figures, and the lauded economic reform, and the crowed-about FDI numbers, the condition of those way, way below the 'poverty line' are seeing any improvement whatsover. The anecdotal evidence is that they are not. The anecdotal evidence says that they are resorting to strategies that damage the body and demean the spirit. They are drinking petrol and breathing fire in alleyways to stay alive.

Thursday, June 15, 2006

Brothers of the South

I have been noticing recently increasing coverage of Egyptian affairs by the Chinese news agency Xinhua. Xinhua is perhaps one of the few rivals to the Egyptian state newspapers for greatest use of that risible phrase, so beloved of non-news agencies, "bilateral ties". Trade between the two countries is increasing, and both are important emerging markets. What is interesting is contained in the thrust of this recent People's Daily article: What President Hu calls "South-South" co-operation. China of course has been for decades a block for the ambitions of Europe and the US on the security council, and is now beginning to flex its economic muscles by building, yes, bilateral ties, in places like Egypt - not traditionally anywhere near its sphere of influence. I expect that, if the Mubarak government was amenable to learning from the Chinese on more than just how to turn around an ailing socialist economy, they'd pick up a thing or two about state repression. China has, since the 1980s, been writing the textbook on how to regenerate economically whilst keeping the same old heads in power, regardless of the democratic impulses of its population. I guess these two are made for each other.

Goodies and Baddies

After a long delay, (allegations have been made of an incident involving our ADSL router and the Nile) we are back in business. First item of interest today is this by Elijah Zarwan, which is an excellent indication that despite the battle-lines having been pretty clearly drawn in Egypt over the past couple of years, reality is always more complex. Elijah reports on testimonies from detainees, who are saying that the security services are not always the monolithic monster that they may seem.

Thursday, May 25, 2006

Status Symbols

[Pillars of Justice - The Judges Club outside the High Court]

This afternoon, two demonstrations of discontent took place within a hundred metres of each other. The first was a vocal and unusually well attended Kifaya! protest on the steps of the Journalists' Syndicate. The second was ten minutes of a silent photo-op on the steps of the High Court from members of the pro-reform Judges' Club.

The first was of a style that has become familiar to activists, journalists and state security over the past couple of years. Slogans, energy, an atmosphere of latent confrontation with the state. Down with Hosni Mubarak, Down with Habib al-Adli. A symbol of ordinary people moved to action by the conditions of injustice in which they find themselves.

The second was of a less familiar style, and was a political statement of a different order of magnitude from the first. This is not to belittle the efforts of Kifaya! and the various organisations who have so bravely and for so long stared down the barrell of state security, but to point out that the nature of the authoritarian state defines even the method of protest against it.

In common with other protest groups, the pro-reform judges led by Zakariya Abdel Aziz do a little symbolic appropriation for effect. Everyone claims ownership of the Egyptian flag - the difference in the judges' case is that they can afford one thirty metres long. And, as is their right as an integral part of the machinery of state, they display proudly the badges of their institution - green sashes, lapel pins and the like. The last symbol is somewhat more elusive, but is evident in the silken handkerchiefs adorning well-tailored suits, dark sunglasses, and the air of well-fed upper-class confidence. They are the symbols of an elite - just not, as it happens, the ruling one.

[A long, long flag of Egypt winds its way up the steps of the High Court]

[Members of the Egyptian Judges' Club assemble to quietly make their point]

[Club President Zakariya Abdel Aziz solemnly leads his colleagues]

[Judges prefer silent protest]

The several hundred of these individuals who stood on the steps of the High Court were an imposing and impressive sight. They were aware of the value of the photo-op, aware of the weight of their station, and aware of the effect of their thus deployed symbols. They are an element of the state unwilling to accede to the notion that the executive is the state.

So whether this dignified battallion represents a coming fight for a meaningful system of justice in this country, or whether such thing has already been lost, time will tell. But today made so very obvious the fact that if the opposition movements are ever to achieve anything against the control of the Mubarak regime, they need symbols like these.

Friday, May 19, 2006

End of an Affair?

It seems like the dust is settling on yet another political 'crisis', and the saga of Judges versus the State is, for now, over. Mahmoud Mekki was acquitted yesterday of the absurd charge of 'disparaging the Supreme Judicial Council'. His partner-in-crime Hisham Bastawissi was merely reprimanded for the same misdemeanour. The verdicts were contrary to what, officially at least, the two pro-reformers expected. Bastawissi, before being struck down by a heart attack on Wednesday, said on Tuesday that he was expecting to be dismissed, and that no negotiations had been undertaken with the SJC.

Last week, I attempted to predict how the regime would steer its way out of this situation, and presented a smart option and a dumb option. The smart option involved making concessions to the judges, acquitting them, and then losing the judicial independence issue within the slothful machinery of state. The dumb option involved making no concessions, and just toughing their way out of it with the help of the security services.

Turns out they did both.

Here's an account of what I witnessed downtown yesterday:

[A security cordon around the high-court prevented protestors getting close enough to be beaten up in front of it]

Having learned from last week’s events that it isn't good for appearances to be beating up protestors in front of the emblem of state justice, the area around the High Court was yesterday totally sealed off. Even High Court staff had difficulty getting to work, and there was little chance that Kifaya! or the Brotherhood were going to be able to show up there. At around 9am an incident had ocurred in Abassiya, and apparently Brotherhood and Kifaya! members had been beaten. Abassiya is a good place for the Central Security Forces (CSF) to kick-off the day’s activities, as the likelihood of journalists being there is slim.

The demonstrators' tactic, in the face of massive police cordons, was to be fluid and pop-up in unexpected places. I met a number of Kifaya! activists who had just returned from a Brotherhood gathering in Galaa street. They then reappeared, about 100-150 of them, where Talaat Harb street runs into the crowded Midan Orabi. As the demo began, with the Islamist slogans and the holding aloft of Qurans (a tactic not favoured by the mid-ranking MB leadership, as it apparently makes them look like fundamentalists) traders hurriedly shut-up-shop, knowing rightly what was coming next. The slogan session lasted about five minutes, and then the baton-charge arrived. A uniformed phalanx pushed the demonstrators back into the square, and then the Biltagiyya were deployed in a pincer movement to beat and drag-off those who hadn't made an escape.

[A Brotherhood member leads demonstrators near Midan Orabi]

[Baton charge]

[Youth employment initiatives in action – Biltagiyya give chase]

The Biltagiyya were relatively few in number, but were wielding truncheons. The protest group rapidly dispersed through the surrounding streets towards Ezbekiyya. Stragglers were dragged off, beaten, kicked and introduced to the back of one of the green meat-wagons. At this point, apparently the police tactic is to remove your mobile phone and ensure that you cannot be seen from the outside. The most vicious beatings reportedly occur inside the trucks used to transport troops to and from downtown.

I followed a small group of mostly Brotherhood members as they attempted to evade the Biltagiyya, and there unfolded a bizarre pursuit through the tiny backstreets of Ezbekiyya. At one point the protestors thought they had gotten away, only to have a surprise attack sprung on them. I saw one feckless individual being dragged away to some unpleasant fate. Over 250 were reportedly arrested during the day.

[Strange pursuit - through the backstreets with Brotherhood fugitives]

Back downtown (the escapees requested that journalists leave them, as they were something of a liability back there) a very stately gathering had been organised by about 20 or so of the Brotherhood's MPs. Making use of their parliamentary immunity, these gentlemen and a small group of sticker-waving Kifaya! activists began to block traffic on Talaat Harb street. The MPs were wearing black sashes that read MPs Are With The Egyptian Judges. The sashes are something of a relatively common feature in political life now, and usually represent some mournful political reality that the wearers are effectively powerless to prevent, such as the extension of Emergency Law last month.

[Brotherhood MPs and Kifaya! members cooperate to block traffic]

It seems as if the heavy artillery of the Brotherhood was wheeled out in support of the Judges just in the nick of time. Essam al-Eryan even made sure that he got himself arrested just to make the point. The Brotherhood make good capital out of this sort of thing, and had the Judges not been acquitted yesterday perhaps the MB would, as was being threatened, have mobilised across the country in response. But perhaps fortunately it doesn't look like it's going to come to that. Because if one thing would make Washington turn a blind eye, and allow the Security thugs to direct brutality with impunity, it would be the large-scale involvement of the Brotherhood.

As the morning turned into early afternoon and tempers began to get shorter on Talaat Harb, I moved down to near the al-Ghad party HQ. In a separate case in the High Court yesterday, their leader Ayman Nour was having his appeal of his fraud conviction rejected. Five years in Jail. Nour came a distant second in last year's Presidential election. Being the dynamo at the centre of a junior party that was of his own making, I wonder if his definite imprisonment now means the end of al-Ghad. Probably.

[The fate of Dr Ayman Nour has, it seems, been sealed]

It is difficult to gauge the ramifications of yesterday's events so soon. The acquittal of the two judges, whose case had become the nexus of all pro-reform and opposition forces, seems to take the wind out of their sails somewhat. It is a limited victory which removes the momentum for real change. That much seems clear. What will happen in terms of legislation to address the concerns of the Judges' Club is anyone's guess. It depends on the mood of the regime and the appetite of Judges for more confrontation. It has to be said that all pro-reform entities have been outplayed. The government has taken a total-war type approach. The physical force element was obvious, and remains a central part of their strategy regardless of EU and US criticism, which is ineffectual bleating at best anyway. The Psy-Ops element has worked well also, intimidating and confusing opponents with alternating silence and threats. And finally the small scraps that the State threw the opposition yesterday in the form of an acquittal and mild punishment might just mean that for the time being, the troublesome protestors will go home, and we go back to business as usual.

Last week, I attempted to predict how the regime would steer its way out of this situation, and presented a smart option and a dumb option. The smart option involved making concessions to the judges, acquitting them, and then losing the judicial independence issue within the slothful machinery of state. The dumb option involved making no concessions, and just toughing their way out of it with the help of the security services.

Turns out they did both.

Here's an account of what I witnessed downtown yesterday:

[A security cordon around the high-court prevented protestors getting close enough to be beaten up in front of it]

Having learned from last week’s events that it isn't good for appearances to be beating up protestors in front of the emblem of state justice, the area around the High Court was yesterday totally sealed off. Even High Court staff had difficulty getting to work, and there was little chance that Kifaya! or the Brotherhood were going to be able to show up there. At around 9am an incident had ocurred in Abassiya, and apparently Brotherhood and Kifaya! members had been beaten. Abassiya is a good place for the Central Security Forces (CSF) to kick-off the day’s activities, as the likelihood of journalists being there is slim.

The demonstrators' tactic, in the face of massive police cordons, was to be fluid and pop-up in unexpected places. I met a number of Kifaya! activists who had just returned from a Brotherhood gathering in Galaa street. They then reappeared, about 100-150 of them, where Talaat Harb street runs into the crowded Midan Orabi. As the demo began, with the Islamist slogans and the holding aloft of Qurans (a tactic not favoured by the mid-ranking MB leadership, as it apparently makes them look like fundamentalists) traders hurriedly shut-up-shop, knowing rightly what was coming next. The slogan session lasted about five minutes, and then the baton-charge arrived. A uniformed phalanx pushed the demonstrators back into the square, and then the Biltagiyya were deployed in a pincer movement to beat and drag-off those who hadn't made an escape.

[A Brotherhood member leads demonstrators near Midan Orabi]

[Baton charge]

[Youth employment initiatives in action – Biltagiyya give chase]

The Biltagiyya were relatively few in number, but were wielding truncheons. The protest group rapidly dispersed through the surrounding streets towards Ezbekiyya. Stragglers were dragged off, beaten, kicked and introduced to the back of one of the green meat-wagons. At this point, apparently the police tactic is to remove your mobile phone and ensure that you cannot be seen from the outside. The most vicious beatings reportedly occur inside the trucks used to transport troops to and from downtown.

I followed a small group of mostly Brotherhood members as they attempted to evade the Biltagiyya, and there unfolded a bizarre pursuit through the tiny backstreets of Ezbekiyya. At one point the protestors thought they had gotten away, only to have a surprise attack sprung on them. I saw one feckless individual being dragged away to some unpleasant fate. Over 250 were reportedly arrested during the day.

[Strange pursuit - through the backstreets with Brotherhood fugitives]

Back downtown (the escapees requested that journalists leave them, as they were something of a liability back there) a very stately gathering had been organised by about 20 or so of the Brotherhood's MPs. Making use of their parliamentary immunity, these gentlemen and a small group of sticker-waving Kifaya! activists began to block traffic on Talaat Harb street. The MPs were wearing black sashes that read MPs Are With The Egyptian Judges. The sashes are something of a relatively common feature in political life now, and usually represent some mournful political reality that the wearers are effectively powerless to prevent, such as the extension of Emergency Law last month.

[Brotherhood MPs and Kifaya! members cooperate to block traffic]

It seems as if the heavy artillery of the Brotherhood was wheeled out in support of the Judges just in the nick of time. Essam al-Eryan even made sure that he got himself arrested just to make the point. The Brotherhood make good capital out of this sort of thing, and had the Judges not been acquitted yesterday perhaps the MB would, as was being threatened, have mobilised across the country in response. But perhaps fortunately it doesn't look like it's going to come to that. Because if one thing would make Washington turn a blind eye, and allow the Security thugs to direct brutality with impunity, it would be the large-scale involvement of the Brotherhood.

As the morning turned into early afternoon and tempers began to get shorter on Talaat Harb, I moved down to near the al-Ghad party HQ. In a separate case in the High Court yesterday, their leader Ayman Nour was having his appeal of his fraud conviction rejected. Five years in Jail. Nour came a distant second in last year's Presidential election. Being the dynamo at the centre of a junior party that was of his own making, I wonder if his definite imprisonment now means the end of al-Ghad. Probably.

[The fate of Dr Ayman Nour has, it seems, been sealed]

It is difficult to gauge the ramifications of yesterday's events so soon. The acquittal of the two judges, whose case had become the nexus of all pro-reform and opposition forces, seems to take the wind out of their sails somewhat. It is a limited victory which removes the momentum for real change. That much seems clear. What will happen in terms of legislation to address the concerns of the Judges' Club is anyone's guess. It depends on the mood of the regime and the appetite of Judges for more confrontation. It has to be said that all pro-reform entities have been outplayed. The government has taken a total-war type approach. The physical force element was obvious, and remains a central part of their strategy regardless of EU and US criticism, which is ineffectual bleating at best anyway. The Psy-Ops element has worked well also, intimidating and confusing opponents with alternating silence and threats. And finally the small scraps that the State threw the opposition yesterday in the form of an acquittal and mild punishment might just mean that for the time being, the troublesome protestors will go home, and we go back to business as usual.

Sunday, May 14, 2006

Fukuyama, Islam and Democracy

The excellent openDemocracy.net has recently been hosting a kind of symposium on the new afterword to The End of History and The Last Man by Francis Fukuyama. A couple of the articles have dealt with the interface between political Islam and the universalising experience of modernity. The upshot, it seems, is that the meeting of political Islam and modernity leads, surprisingly, to democracy.

First this piece, a rather hopeful paean to the democratic urge by Saad Eddin Ibrahim. Secondly, a sharper analysis by Olivier Roy. Saad deals directly with Egypt, and, I think, misses the point. Roy avoids mention of Egypt specifically, but the logic of his argument meshes very finely with the Brotherhood-State dynamic that has been unfolding here.

In his piece, Dr Ibrahim posits modernity VERSUS theocracy and autocracy. In his, Roy conflates modernity and democracy.

Well, both neo-fundamentalists and authoritarian regimes are products of modernity, not intrinsically prior to it, so the suggestion that the true application of modernity (in the form of neo-liberal democracy) will see them off is misguided. And the idea that modernity brings automatically democracy is contrary to one of Roy's keenest theses.

The first view is congruent with a whole set of imaginative constructions, which basically transform complex reality a digestible, manageable entity. There is the modern world, which is industrialised, liberal, democratic. It is geographically specific, usually meaning, say, Europe and North America. Then there is the world to which modernity is being brought, and which exists in a transition stage between pre-modern and modern reality - as if there is a line that can be crossed or a whistle that can be blown when it is reached.

So, according to a view like Dr Ibrahim's, Egypt's problem is that society is not modern enough, and that it has not progressed far enough along a line that departs from pre-modern social norms and arrives somewhere marked 'democracy'. The problems of society, associated with and caused by the authoritarian state, are teething troubles along a developmental curve.

This might be persuasive if you could plot Dr Ibrahim's two points of theocratic jihadists and autocratic rulers on axes that ignored the reality of Egypt's complex and ongoing relationship with external political actors. It might be persuasive if you thought that the regimes of Mubarak/Sadat and Nasser were purely Egyptian inventions and had nothing to do with the geo-political mess that Egypt has so frequently been in.

But jihadists, and authoritarian government are a product of Egypt's interaction with external actors (or, if you like, with its interaction with modernity), not things that lie passively waiting to be changed by it.

First, government. The modern Egyptian technocratic state owes much in both design and practice to external actors of many kinds. In its design, it draws on French and British legal codes, Soviet style bureucractic structure, and neo-liberal (and specifically American) theory when it comes to planning for economic development. For sure, authoritarianism was honed in Egypt during the alignments of the Cold War, but now they are buttressed by a technocratic ability that comes as much from USAID as anywhere. In practice, it is allowed to be authoritarian, and in some cases required to be so, by the main actors in the geopolitical theatre of the Middle East. Egypt's perceived tension between say, political Islam and democratisiation is managed by the application of authoritarian government. The State Department would have it no other way.

Secondly, Jihadists, or shall we say 'violent political Islam' derives its millenial force from a perception of a power mismatch between the controllers of modernity and its recipients. But in their geographical dislocation, in their dismantling of societal links, in their empowerment of the individual as agent of change, and in their appropriation of technology as agents of destruction, organisations like Jamma Islamiyya (from which grew many other such groups) were/are thoroughly modern in themselves. Again, they are not passive actors waiting for the forces of modernity to change them.

Olivier Roy has been one of the first to realise that political Islam is not external to modernity, but actively involved in it. Here, however, he conflates modernity and democracy. The very arguments he makes here to suggest the "slow but genuine internalisation of liberal and democratic values" he has used before to argue the internalisation of modernity. We see the assumption that modernity IS democracy, despite the acute realisation that modernity has produced other, quite antagonistic philosophies.

Of course, one must make the narrative arc. The practitioners of geopolitics would cease to function if the complexity of reality were allowed to confuse action. Indeed, 'conflate' and 'confuse' are etymologically related.

First this piece, a rather hopeful paean to the democratic urge by Saad Eddin Ibrahim. Secondly, a sharper analysis by Olivier Roy. Saad deals directly with Egypt, and, I think, misses the point. Roy avoids mention of Egypt specifically, but the logic of his argument meshes very finely with the Brotherhood-State dynamic that has been unfolding here.

In his piece, Dr Ibrahim posits modernity VERSUS theocracy and autocracy. In his, Roy conflates modernity and democracy.

Well, both neo-fundamentalists and authoritarian regimes are products of modernity, not intrinsically prior to it, so the suggestion that the true application of modernity (in the form of neo-liberal democracy) will see them off is misguided. And the idea that modernity brings automatically democracy is contrary to one of Roy's keenest theses.

The first view is congruent with a whole set of imaginative constructions, which basically transform complex reality a digestible, manageable entity. There is the modern world, which is industrialised, liberal, democratic. It is geographically specific, usually meaning, say, Europe and North America. Then there is the world to which modernity is being brought, and which exists in a transition stage between pre-modern and modern reality - as if there is a line that can be crossed or a whistle that can be blown when it is reached.

So, according to a view like Dr Ibrahim's, Egypt's problem is that society is not modern enough, and that it has not progressed far enough along a line that departs from pre-modern social norms and arrives somewhere marked 'democracy'. The problems of society, associated with and caused by the authoritarian state, are teething troubles along a developmental curve.

This might be persuasive if you could plot Dr Ibrahim's two points of theocratic jihadists and autocratic rulers on axes that ignored the reality of Egypt's complex and ongoing relationship with external political actors. It might be persuasive if you thought that the regimes of Mubarak/Sadat and Nasser were purely Egyptian inventions and had nothing to do with the geo-political mess that Egypt has so frequently been in.

But jihadists, and authoritarian government are a product of Egypt's interaction with external actors (or, if you like, with its interaction with modernity), not things that lie passively waiting to be changed by it.

First, government. The modern Egyptian technocratic state owes much in both design and practice to external actors of many kinds. In its design, it draws on French and British legal codes, Soviet style bureucractic structure, and neo-liberal (and specifically American) theory when it comes to planning for economic development. For sure, authoritarianism was honed in Egypt during the alignments of the Cold War, but now they are buttressed by a technocratic ability that comes as much from USAID as anywhere. In practice, it is allowed to be authoritarian, and in some cases required to be so, by the main actors in the geopolitical theatre of the Middle East. Egypt's perceived tension between say, political Islam and democratisiation is managed by the application of authoritarian government. The State Department would have it no other way.

Secondly, Jihadists, or shall we say 'violent political Islam' derives its millenial force from a perception of a power mismatch between the controllers of modernity and its recipients. But in their geographical dislocation, in their dismantling of societal links, in their empowerment of the individual as agent of change, and in their appropriation of technology as agents of destruction, organisations like Jamma Islamiyya (from which grew many other such groups) were/are thoroughly modern in themselves. Again, they are not passive actors waiting for the forces of modernity to change them.

Olivier Roy has been one of the first to realise that political Islam is not external to modernity, but actively involved in it. Here, however, he conflates modernity and democracy. The very arguments he makes here to suggest the "slow but genuine internalisation of liberal and democratic values" he has used before to argue the internalisation of modernity. We see the assumption that modernity IS democracy, despite the acute realisation that modernity has produced other, quite antagonistic philosophies.

Of course, one must make the narrative arc. The practitioners of geopolitics would cease to function if the complexity of reality were allowed to confuse action. Indeed, 'conflate' and 'confuse' are etymologically related.

Thursday, May 11, 2006

Two Scenarios for the Week Ahead

The events in Cairo today speak for themselves. They represent the advanced stages of an authoritarian government's utter loss of moral legitimacy. All agents of opposition to the state are now being violently confronted. Many commentators speak of a 'crisis point' being reached. In that case, how to calculate, or speculate, as to what will happen next?

Let's imagine two scenarios:

Scenario One:

Anxious to ameliorate a political situation that is rapidly becoming uncontrollable, even with the assistance of the massive security apparatus, the state attempts a compromise with the two actors who now hold the hopes of almost the entire opposition - Hisham Bastawissi and Mahmoud Mekki. In the days until the date set for the next hearing of the Supreme Judicial Council (18th May) negotiations take place which aim to placate the judges by acceding to their preliminary demands (allowing their own staff in court, toning down the security presence, and letting all the Kifaya demonstrators who have faced riot police on their behalf for the past two weeks out of jail) and dangling the carrot of judicial reform. The hearing then acquits the judges of bringing the judiciary into disrepute, and some kind of vague promises are made about investigating the 2005 election. Both the promises of investigating the conduct of the elections and instigating judicial reform take for ever to even begin, and the whole opposition movement loses momentum and, for the time being, shuts up. The regime lives to fight another day, and very little changes, although cosmetically it seems as if reforms are being made. The State Department is happy, and things return to relative normality.

Scenario Two:

In the days until the next hearing, the government displays an inability to think strategically because it is so spooked by being challenged so brazenly in the first place. After all, the judges are in themselves an arm of the regime. It just so happens that some of them no longer see it that way. So no practical concessions are made by either the Ministry of Justice, or the Presidency, or the Ministry of the Interior. The judges increase their media campaign, and become increasingly famous and write more op-eds in western newspapers. The hearing goes ahead on 18th May, even though Mekki and Bastawissi refuse to attend, and it passes a guilty verdict on them in absentia. They are dismissed from their posts and join the ranks of disenfranchised activists holding posters on the street. Security continues to arrest, beat, harass and intimidate anyone that so much as dares to pass in front of their tea-stands in Talaat Harb. The remaining troublesome judges are fingered by the SJC, and are either dismissed or they back down, fearful for their livelihoods and pensions. With no rallying-point left, Kifaya et al go home. The State Department makes noises, but because Egypt is such a strategic ally in the war on terror (that policy is distinguished by its effectiveness, no?) no real action is taken. Things return to relative normality.

So, which scenario wins? Is there a third way? Will things NOT return to normal after all?

Let's imagine two scenarios:

Scenario One:

Anxious to ameliorate a political situation that is rapidly becoming uncontrollable, even with the assistance of the massive security apparatus, the state attempts a compromise with the two actors who now hold the hopes of almost the entire opposition - Hisham Bastawissi and Mahmoud Mekki. In the days until the date set for the next hearing of the Supreme Judicial Council (18th May) negotiations take place which aim to placate the judges by acceding to their preliminary demands (allowing their own staff in court, toning down the security presence, and letting all the Kifaya demonstrators who have faced riot police on their behalf for the past two weeks out of jail) and dangling the carrot of judicial reform. The hearing then acquits the judges of bringing the judiciary into disrepute, and some kind of vague promises are made about investigating the 2005 election. Both the promises of investigating the conduct of the elections and instigating judicial reform take for ever to even begin, and the whole opposition movement loses momentum and, for the time being, shuts up. The regime lives to fight another day, and very little changes, although cosmetically it seems as if reforms are being made. The State Department is happy, and things return to relative normality.

Scenario Two:

In the days until the next hearing, the government displays an inability to think strategically because it is so spooked by being challenged so brazenly in the first place. After all, the judges are in themselves an arm of the regime. It just so happens that some of them no longer see it that way. So no practical concessions are made by either the Ministry of Justice, or the Presidency, or the Ministry of the Interior. The judges increase their media campaign, and become increasingly famous and write more op-eds in western newspapers. The hearing goes ahead on 18th May, even though Mekki and Bastawissi refuse to attend, and it passes a guilty verdict on them in absentia. They are dismissed from their posts and join the ranks of disenfranchised activists holding posters on the street. Security continues to arrest, beat, harass and intimidate anyone that so much as dares to pass in front of their tea-stands in Talaat Harb. The remaining troublesome judges are fingered by the SJC, and are either dismissed or they back down, fearful for their livelihoods and pensions. With no rallying-point left, Kifaya et al go home. The State Department makes noises, but because Egypt is such a strategic ally in the war on terror (that policy is distinguished by its effectiveness, no?) no real action is taken. Things return to relative normality.

So, which scenario wins? Is there a third way? Will things NOT return to normal after all?

Monday, May 01, 2006

The Full Force of the Law

On Thursday last week, in the wake of the Dahab bombings, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak announced that he would fight terrorism with the "full force of the law." Early yesterday morning, Egyptian security troops reportedly shot dead three men in North Sinai during a counter-terrorism operation. Yesterday afternoon, Prime Minister Ahmad Nazif announced that the government would 'ask' the People's Parliament to extend the operation of Emergency Law by two years. Emergency Law, which denies Egyptian citizens basic rights, has been in force solidly for twenty five years. In the last week dozens of demonstrators - who have been protesting against the state's prosecution of two Cassation Court judges – have been arrested by the security services, and many have just been beaten by the plain-clothes rent-a-thugs who are becoming all too familiar in downtown Cairo.

[The sartorial sign of impending trouble - the biltagi boys line up]

Today, a demonstration was scheduled for 5pm outside the Talaat Harb St branch of the Omar Effendi department store. The venue was intended to be symbolic of the state's corrupt sell-off of public companies. No such demonstration materialised, although there were a handful of Central Security trucks parked at the end of the street just in case. It soon became evident that a 'demo' was taking place on the balcony of the Nasserist Party offices slightly further up Talaat Harb St. Cue for the assembled ranks of CSF troops and biltagiyya to jog lazily up the street and barricade the half-dozen or so noisy Nasserists into their building.

[An afternoon jaunt for State Insecurity]

At this point the Central Security hierarchy, hardmen and hired help began to usher journalists, cameramen and passers-by up toward the end of the street in the usual semi-threatening manner. When the middle-aged men in white uniforms and gold brocade start to clumsily urge foreign journalists away from any particular spot, it is reasonable to assume that something grim is in the pipeline. But today it was hard to see exactly who the hardmen would actually be picking on. A lot of standing around was happening, a lot of self-important posturing from over-muscled and under-brained goons with pistol belts. Perhaps there was a hardened core of trouble-makers just round the corner, waiting to pitch the Egyptian state into turmoil.

[The charm offensive begins - in a black ribbed tank-top]

Or perhaps there was a ragtag gang from the Nasserist party, offering the usual fayre of noisy nostalgia for a man (and an Egypt) that has been dead for nearly thirty-six years. Just in case they should explode forth from their HQ with hitherto undemonstrated vigour, the entrance was surrounded by troops for over an hour. It's hard to imagine the Nasserist party posing much of a threat to public order, but it was May Day after all, and things can easily get out of hand, so perhaps it was best to pen them in for a while.

[Nasserists going nowhere]

About a fifty metres away, above the panelled environs of Groppi's cafe, the Ghad party's efforts were in full swing. But the interior of the Ghad party's HQ was plush, and dusty, and empty. Is this really the party that produced the runner-up in last year's Presidential election? Or is it that Ayman Nour produced the party, and now that he is languishing in prison, his creation is rapidly falling apart? I met with a Nasserist party sympathiser who was just standing on the Ghad balcony for the view, making up the numbers. Those that were present (about a dozen, by no means all party members) were making an effort to arouse the interest of passers-by below, and to rile the bemused inhabitants of the State Security wagons parked on the square. They were marginally more successful with the latter than the former.

[The lonely beat of a Ghad flag-waver]

On the street below, the police chiefs and security managers were conducting affairs with a fairly calm, workaday attitude. The management of small-scale public discontent has become business as usual over the past couple of years for these individuals. And a small service industry has sprung up to cater to their needs. Tables and chairs appear on the street, and cold drinks and tea are served to police and CSF staff without much fuss. A waistcoated waiter was even seen ferrying chilled water and other assorted beverages to the walkie-talkie men as the evening wore on. Despite the large numbers of troops, and the reports of beatings, and the arrests, public dissent in Egypt is not even close to the point where the authorities are really rattled. They can just sit back, have some tea, and wait for it all to go away.

[A Central Security control centre, today]

So in the light of terrorist attacks, mass arrests, and the very real and visible retrenchment of the state into the old dictatorial patterns, it has to be said that the secular opposition in Egypt is in a very parlous state, if this is the best they can muster. The official channels of protest (i.e. the parliament) are still as ham-strung as they have ever been. Protest in those chambers at the actions of government are even more symbolic than banners on the streets. But now, in 2006, it seems that not even those banners can be assembled in any great number, and that apathy, defeatism and the long arm of the Police State has pummeled the secular opposition into near-submission. The Emergency Law has been remarkably effective at keeping Mubarak in government. And judging by today's non-event, the opposition parties are hardly able to raise a whimper in response.

[The sartorial sign of impending trouble - the biltagi boys line up]

Today, a demonstration was scheduled for 5pm outside the Talaat Harb St branch of the Omar Effendi department store. The venue was intended to be symbolic of the state's corrupt sell-off of public companies. No such demonstration materialised, although there were a handful of Central Security trucks parked at the end of the street just in case. It soon became evident that a 'demo' was taking place on the balcony of the Nasserist Party offices slightly further up Talaat Harb St. Cue for the assembled ranks of CSF troops and biltagiyya to jog lazily up the street and barricade the half-dozen or so noisy Nasserists into their building.

[An afternoon jaunt for State Insecurity]

At this point the Central Security hierarchy, hardmen and hired help began to usher journalists, cameramen and passers-by up toward the end of the street in the usual semi-threatening manner. When the middle-aged men in white uniforms and gold brocade start to clumsily urge foreign journalists away from any particular spot, it is reasonable to assume that something grim is in the pipeline. But today it was hard to see exactly who the hardmen would actually be picking on. A lot of standing around was happening, a lot of self-important posturing from over-muscled and under-brained goons with pistol belts. Perhaps there was a hardened core of trouble-makers just round the corner, waiting to pitch the Egyptian state into turmoil.

[The charm offensive begins - in a black ribbed tank-top]

Or perhaps there was a ragtag gang from the Nasserist party, offering the usual fayre of noisy nostalgia for a man (and an Egypt) that has been dead for nearly thirty-six years. Just in case they should explode forth from their HQ with hitherto undemonstrated vigour, the entrance was surrounded by troops for over an hour. It's hard to imagine the Nasserist party posing much of a threat to public order, but it was May Day after all, and things can easily get out of hand, so perhaps it was best to pen them in for a while.

[Nasserists going nowhere]

About a fifty metres away, above the panelled environs of Groppi's cafe, the Ghad party's efforts were in full swing. But the interior of the Ghad party's HQ was plush, and dusty, and empty. Is this really the party that produced the runner-up in last year's Presidential election? Or is it that Ayman Nour produced the party, and now that he is languishing in prison, his creation is rapidly falling apart? I met with a Nasserist party sympathiser who was just standing on the Ghad balcony for the view, making up the numbers. Those that were present (about a dozen, by no means all party members) were making an effort to arouse the interest of passers-by below, and to rile the bemused inhabitants of the State Security wagons parked on the square. They were marginally more successful with the latter than the former.

[The lonely beat of a Ghad flag-waver]

On the street below, the police chiefs and security managers were conducting affairs with a fairly calm, workaday attitude. The management of small-scale public discontent has become business as usual over the past couple of years for these individuals. And a small service industry has sprung up to cater to their needs. Tables and chairs appear on the street, and cold drinks and tea are served to police and CSF staff without much fuss. A waistcoated waiter was even seen ferrying chilled water and other assorted beverages to the walkie-talkie men as the evening wore on. Despite the large numbers of troops, and the reports of beatings, and the arrests, public dissent in Egypt is not even close to the point where the authorities are really rattled. They can just sit back, have some tea, and wait for it all to go away.

[A Central Security control centre, today]

So in the light of terrorist attacks, mass arrests, and the very real and visible retrenchment of the state into the old dictatorial patterns, it has to be said that the secular opposition in Egypt is in a very parlous state, if this is the best they can muster. The official channels of protest (i.e. the parliament) are still as ham-strung as they have ever been. Protest in those chambers at the actions of government are even more symbolic than banners on the streets. But now, in 2006, it seems that not even those banners can be assembled in any great number, and that apathy, defeatism and the long arm of the Police State has pummeled the secular opposition into near-submission. The Emergency Law has been remarkably effective at keeping Mubarak in government. And judging by today's non-event, the opposition parties are hardly able to raise a whimper in response.

Saturday, April 29, 2006

The $100 Laptop in Egypt - Development or Diversion?

A small delegation from an organisation known as One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) visited Egypt this week, and met with various dignitaries and business leaders. Their purpose was to establish links with ICT and education professionals in the country, as Egypt is to be one of the pilot nations (along with Brazil and Thailand) in OLPC's $100-laptop scheme due to start later this year.

The basic idea of the scheme is to develop a portable personal computer for the needs of education in the developing world, manufacture it at a very low cost ($100) and sell it to governments for distribution amongst the school-age population. It sounds like a very good idea. It also directly addresses a central area of first-world angst since the internet began to 'revolutionize' our lives some ten years ago – the digital divide.

The Digital Divide is the notion that, as the individuals and economies of first-world countries make rapid advances in their co-operative ability through the internet, the developing world is left further and further behind because they do not have access to the technology. Recently, some observers have claimed that due to the availability of cheap telephony and locally manufactured hardware, certain parts of the developing world are catching up.

Whether or not that is true, OLPC is an organisation with anxiety over the digital divide at its very heart. It is the project, in part, of MIT founder and chairman Nicholas Negroponte. If the name sounds familiar, it is because he is the brother of John Negroponte, the US Director of National Intelligence and former ambassador to Iraq. OLPC is, self proclaimedly, "a new, non-profit association dedicated to research to develop a $100 laptop—a technology that could revolutionize how we educate the world's children".

Negroponte is visionary about the potential of technology to improve educational standards in places where the state fails its children. He has two basic principles –which you can read in his article in The Economist's "The World in 2006". The first is that "education is always part of the solution" - to what problem he does not specify, but we might assume he means "a lack of development". The second is that "learning, as well as coming from 'top-down' institutions also comes from exploration and independence".

It is hard to take issue with either of these pleasant banalities. What has, as yet, to be made clear is the role that the implantation of ICTs into locations where they are usually unobtainable has in encouraging either statement to become reality.

The technological side of OLPC is somewhat impressive. It is a feat of manufacturing and logistics to be able to create a functioning laptop for such little money – and the kind of feat one might expect from an eminent institution of technocracy such as MIT. The first-generation product is slated to be a Linux-based 400MhZ AMD machine, with 128Mb of SDRAM, super-low energy consumption and the ability to be cranked by hand. If you can remember the Bayliss radio, the look of the "Green Machine" as it is called, is very similar. OLPC places, naturally, a lot of emphasis on Open Source Software, although the educational content with which the machines will come equipped has not been confirmed. It is hard to find examples of quality Open Source educational software, but there are programmes which can parallel proprietary applications such as Microsoft Office and Adobe CS.

But when it comes to the interface between technology and the real world, OLPC is, unfortunately, a triumph of optimism over clear thinking.

It relies on a couple of imaginative constructions, ways of seeing the world which obscure the real conditions in developing countries, and the effects which international development produces in them. The first of these is that we, in the first world, live in a kind of techno-utopia where modernism has all but obliterated opposition to the 'rule of experts', and where our lives have been immeasurably improved by the advent of ICTs and the internet.

The second of these, which follows from the first, is that the introduction of technology into places where it is not being indigenously developed will make the lives of the recipients immeasurably better also.

The mere naming of these constructs should make the fallacy upon which so much international development is predicated obvious immediately. Common sense says that neither of these statements are necessarily true. However, a third construct is key to the OLPC project, and it is the simple belief that ICTs help learning. Now, I had thought that "Getting the Internet Helps with Your Homework" was just a particularly perfidious advertising suggestion to shift Dells and Hewlett-Packards, but it seems to have filtered its way into the development community without much critical evaluation.

Computers can, it is true, assist educational development in a constructive and supervised atmosphere. It can do so where the software, logistical support and know-how are present and affordable. But it is ridiculous to imply that ICTs can circumvent the fundamental deficits in any given national education system – which are present due to a myriad of social and economic difficulties. In Egypt, these deficits take the form of enormous class sizes, dilapidated classrooms, badly paid and under-motivated teachers, an overbearing secondary exam system and a bloated university sector. All the computer hardware in the world can do nothing about any of these. To claim that a $100 laptop can "revolutionize" education, in such an environment is well-intentioned, but foolish.

So, these are the structural difficulties that the Egypt's education system already struggles with, before it might be confronted with the difficulties of implanting large quantities of odd-looking computers. By far and away the most glaring of these secondary difficulties is literacy. Literacy is the elephant in the boardroom when international ICT corporations are doing business with the Egyptian education sector – something left unmentioned because it is too large a problem to contemplate. Granted, it is a problem that is being managed to an extent, but there is still a significant part of the female population particularly that isn't getting any schooling at all, much less being taught how to manipulate eBay.

Then we have the following headaches, in no particular order: The presence or otherwise of resources to maintain hardware, to purchase (or more likely pirate) international-standard software (why should the developing world have to muddle along with home-made Open Source programming when the first world gets the best?), the ability to train users in new applications, the ability to critically evaluate the plethora of internet sources, the money to pay for telephony or ADSL rental (dial-up in Egypt is reasonably cheap, broadband is not), the guaranteed reliability and autonomy of service providers, and the ability to take advantage of e-commerce through modern retail banking and affordable credit. It's quite a list, and it could be longer.

The above are basic requirements for an individual to be able to fully take advantage of the information age. Will OLPC provide these requirements? No. The simple reason is that the hardware itself is essentially second-tier, and is being aimed at the infrastructural level of the remote village, where electricity is at a premium (hence the hand-crank) and where the slated Wi-Max connectivity might conceivably be of use because of the absence of normal copper-wire telephony. But the ability to use such technology effectively is by no means automatically present in the places where the hardware seems destined for, and such ability is really only present at a much higher level of infrastructural development - i.e. in the lower middle classes of urban areas. A computer is something of an inappropriate addition to a household that does not have running water. The design of the OLPC project seems to rest on an odd image of the recipient as someone with a high level of basic education and fluent English, but who lives in a mud-hut in the middle of nowhere.

But who knows where the OLPC hardware will actually end up in Egypt. Despite the aspirations to sidestep 'top-down' learning, the OLPC machines will be distributed by the Egyptian government, who may have priorities other than the equitable education of its masses in mind. Now, this leads to the final point. At $100 each, the OLPC computers are to be sold at cost to, presumably either the Ministry for Education or the Ministry of ICTs. With the preliminary order reportedly one million units, this will set the purchaser back, of course, a hundred million bucks. The Minstry of Education has published its estimated spend for the five year period 2002-2007, and such a figure represents nearly 8% of its annual budget. It wasn't included, however, because OLPC was only thought-of last year.

So it is reasonable to assume that if the order does proceed this way, it will be at the expense of an increase in teachers' salaries, or much-needed infrastructural repairs. Even if the money materialises from international donors, it is still a heinous waste in the light of the country's obvious educational shortcomings, and would be money spent chasing the chimera of technological progress instead of shoring up real, traditional schools.

If the idea of OLPC seems immediately appealing, this is because in the first world we are all, almost automatically, part of the techno-utopian dream to which OLPC belongs. But the first world has all of the other resources to make use of the internet and ICTs - and the 15 million school children of Egypt mostly don't. So it might be useful to get the reading and the writing done first, and worry about the badges of techno-modernity later.

Thursday, April 27, 2006

Band Camp Meets Boot Camp – It's the State versus the People Again

Judging by the news headlines, the last few weeks in Egypt have been fairly tumultuous. Let's make a list of events: A fatal stabbing in an Alexandrian church, followed by tri-partite riots between Christian youths, Muslim youths, and State Security; The continued harrassment and incarceration of two of the country's top judges; The continued harrassment and incarceration of the country's more 'problematic' journalists; A triple bomb attack in the Sinai resort of Dahab, rapidly followed by what seemed like impromptu suicide-bombings on Multinational forces further north; Unconfirmed reports of shooting and rioting in the Delta.

Not bad for the "Land of Peace", eh? None of these events are, in themselves, especially surprising or unusual here. You could pluck similar stories out of just about any newspaper archive from the last twenty or more years. And yet, the leprous Mubarak regime lumbers on. So it isn't surprising either to have turned up at the Journalists' Syndicate on Wednesday night, camera in hand, to find an immense (we are talking at least 1000 troops) security presence. CSF (Central Security Forces – or State Insecurity as I like to call them) trucks were parked two-deep on Ramses Street, and in the smaller streets surrounding the syndicate lurked lines and lines of uniformed CSF to back up the ranks already in front of the building.

What eminent threat were they there to guard against? About 60 mostly middle-aged Kifaya! and other assorted 'opposition movement' groups (and the ever present guy-in-the-wheelchair) gathered on the steps to shout the usual anti-regime slogans. The immediate context is the arrest and 'hearing' of charges against Mohammad Mekki and Hisham al Bastawissi, two judges who happened to be overly critical of the government's handling of the 2005 election count. The wider context is that Kifaya! (means "Enough!") and a fairly motley assortment of Islamists, Nasserists, Liberals and intellectuals have been staging street protests of varying size for the past two years. The judges' hearing is just the latest in a long line of injustices perpetrated by the state. So they get together and shout "Down with Mubarak" and "Down with Habib al-Adly" (most-hated vizier of the Interior), and sometimes a more amusing slogan, something like "Hey Condoleeza, Get Mubarak A Visa", referring of course to a fond but hopeless wish that the ageing dictator would just abdicate to the States, the only place where he seems to be appreciated.

[Prominent film producer Sabry al Samak rouses the assembled dozens]

[Prominent film producer Sabry al Samak rouses the assembled dozens]The familiar atmosphere of cameraderie and badly organised 'outrage' pervaded, as the chief chant-leaders vied for control of the megaphone. Everyone knows each other by now - some of them even like each other. And all of this noise and friendly clamour watched over by the hoards of glowering, illiterate grunts picked up from the dusty backroads of Upper Egypt, none of them having a clue what's going on, looking fairly miserable. It's band-camp meets boot-camp.(see shots below)

[Protestors sit it Out facing State Insecurity]

[Protestors sit it Out facing State Insecurity] [Badly paid, badly equipped, miserable farmers' third sons pressganged into coralling protestors in Cairo]

[Badly paid, badly equipped, miserable farmers' third sons pressganged into coralling protestors in Cairo] [More of same. Multiply this by several, perhaps tens thousands and you have the face of state control]

[More of same. Multiply this by several, perhaps tens thousands and you have the face of state control]You could say that the authorities of the state were taking extra precautions to ensure public order in a particularly tense and emotional period of public life. Or you could say that, as usual, they were using a hammer to crack a nut –it's the only way they knows.

As the evening wore on everyone was waiting for the biltagiya (a particularly unpleasant face of state-insecurity, un-uniformed thugs wearing plaid-shirts and a miasma of B.O. hired for the evening to tag-team some unsuspecting Kifaya chant-leader in an alleyway). A small side-demonstration, outside the main cordon, ended up in a couple of arrests and some hysterics among the honking traffic by the High Court. Two guys with some axe or other to grind get baton-charged by the fey-looking CSFs (below).

[Run Away! Run Away!]

[Run Away! Run Away!]In the end, the demonstrators were dispersed one-by one by the biltagiya. As there were so few of them, it didn't apparently take long. As a movement that expresses the anger and discontentment of Egyptians with their government, Kifaya is a noble, but ineffective rump. It's not surprising. I was told of how the CSF deliberately pick on new recruits, to discourage others from joining. They have a narrower and narrower platform, if they ever had one to begin with. One Kifaya activist noted later in the Greek Club (a shabby, moth-eaten memorial to some liberal, intellectual era now long passed) that the judges are all they have left. The others have either been lost (the election) or are almost without hope (the Emergency Law). Even the official opposition has mostly been either imploding ( Wafd) or spending rather a lot of time in Jail (al-Ghad).

If all you could see in Egypt was the bombs and the headlines and the massive ranks of CSF, you might judge that the regime was in its death-throes. It has, after all, been twenty-six years. But to stand and appreciate the flaccidity of the opposition is to realise that no matter how sclerotic the regime may be, it's probably going to be around just as long as it wants to be.

Sunday, April 16, 2006

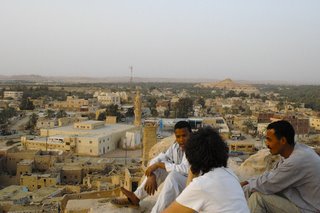

Siwa - Here Comes Progress

There are a couple of things evident upon arriving at the adobe-brick bus station in Siwa, hot off a nine-hour slog from Alex. The first is that the oasis — over 500km from Cairo and just 50km from Libya — is not much like anywhere else in Egypt. The second thing that is evident is that this state of affairs won’t last for long.

Siwa’s uniqueness is a product of its sheer isolation. Not even the demotic Arabic speech of Cairo, which has conquered far and wide in Egypt, is in the ascendancy here. A rough and ready Berber parlance is still more commonly heard in Siwa’s market places and alleyways, and the town’s ‘feel’ is more of the Maghreb than the Nile Valley. Such isolation bequeaths a kind of autonomy, and Siwa has always been less than enthusiastic about the rule of outsiders. In fact, the writ of the modern Arab Republic of Egypt only really fully included the oasis after a proper road was built from Marsa Matruh in the 1980s.

The broad plain, blanketed in date and olive groves, and surrounded by two large freshwater lakes is by any standard an exceptionally beautiful place. It supports a settlement of about 23,000 people, who are mostly involved in an agriculture which has little to do with the modern world, and who represent a culture more introverted and conservative than readily found elsewhere in Egypt.

At the centre of the settlement is a kind of arcane symbol of the oasis’ antiquity — the deserted citadel of Shali, now a crumbling, five storey relic of a harsher desert past. Even though Shali has been mostly abandoned since heavy rains in 1926, the town’s poorest, landless inhabitants still live in its dusty periphery, with teenage boys lurking at each corner to escort visitors around their precarious asset.

It is easy to see how Siwa’s possession of natural attractiveness, the relics of antiquity, and a cultural indifference to modernity make it something more than just a settlement, more than just an isolated society. In the eyes of the outside world, Siwa is a tantalising glimpse of a pristine culture, and one that is increasingly attainable. In short, it is rapidly becoming a destination.

When it comes to the raw material needed for a thriving tourist industry, Egypt has an embarrassment of riches.

Nevertheless, Siwa is a relatively untapped resource, and remains a highly valuable commodity in a market that is characterised by seemingly unstoppable growth. The Ministry of Tourism’s figures claim that Egypt welcomed 8.6m tourist arrivals in 2005 and is planning for 14m by 2011.

Such a volume of visitors, and the cash that it represents is a powerful motor for change – and arguably the sole motor for change in a place like Siwa.

Tourism, as one of its side-effects, generates infrastructure. And infrastructure generates, albeit in an indirect way, social change. Siwa’s exposure to social mores other than its own, and its political isolation were irrevocably changed with the completion of the road from Marsa Matruh. Now, it is expected that the newly refurbished airport in Siwa will begin to receive tourist charter flights, cutting out the long and daunting road trip from the north coast.

The process is fairly obvious – if you have a desirable resource in an expanding market, you exploit it. The question is how that process of ‘development’ will be managed, and by whom. In Siwa, even those that stand to gain by an influx of tourists are ambivalent about the airport. One hotelier admitted to me that Siwans are pleased to welcome a limited number, but are nervous about losing control of the process – “Of course things will be very different when they open the airport” he said, “And we will welcome the extra guests as we can. But we also know the trouble that it can bring”.

It is easy to bemoan the blight of modern tourism, voraciously devouring ‘experiences’ and ‘cultures’ at the net expense of local societies. And in Siwa there is in fact a model of sustainable touristic development, in the shape of an ‘Eco-Lodge’ on the outskirts of town. The problem however is that sustainable tourism is hardly a mass market – in fact the comfort of knowing you are exploiting nothing and no-one in Siwa comes at a hefty premium. The Adrere Amellal lodge charges about $400 a night.

If there is a model of responsible development in this respect, which could be hoped for the relatively un-developed Siwa, it is hard to find in Egypt.

In addition to the accommodation needs of foreign visitors, the middle classes of Cairo and Alexandria are fuelling a second-home construction boom that is rapidly covering the country’s coastlines with identikit holiday homes. On the road from Alexandria to Marsah Matruh, there now exists a slick of such ‘tourist villages’ that is 100km long and 2km deep from the shore. The ‘villages’, which exist behind 30ft walls are situated in stark contrast to the filthy slums of service workers and construction labourers that lie outside them on the far side of the highway. There is scant physical evidence of profit from such projects going anywhere apart from the pockets of property developers in Cairo and abroad.

If an indication is needed of the priorities of government when it comes to this kind of development, a look at the newest construction project in Siwa is pretty instructive. It is called the Mubarak Sports Village, and is as odd a monument to dictatorial paranoia as this writer has seen.

As an unwieldy reminder of the structure of power and consent in Egypt, it is perfect. The ‘village’ (in a town where household running water and electricity are by no means universal) is equipped with a stadium that looks as if it could hold at least 20,000 (Siwa pop. 23,000) and is painted bright pink. There wasn’t much sign of any sport happening within its confines.

This edifice, which so proudly announces the beneficence of the First Family is closed to the public, and has been pretty much since it was completed. It is occupied solely by wall-eyed infantry grunts who look like they wish they had never heard of Siwa. A token, if one was needed, about who holds the ear of the ruling party. A local businessman, when asked what the Sports Village was all about answered: “The Government, it has some crazy idea about what kind of country this is. This thing is ridiculous, it’s a delusion.”

So the question posed by all of this is, “Is bad development better than none at all?” Judging by recent developments, bad development is what Siwa is going to get. Is the trickledown effect of more visitors (potentially better water and sanitation facilities, and a increased cash-flow to Siwan people) worth the distortions in the local economy?

As a location somewhere between the past and modernity, and a location small enough to witness change happen ‘live’, Siwa is worth watching for the answers to these questions. Just don’t ask anyone about the local football team.

Saturday, April 15, 2006

Sectarian Violence in Alexandria

Yesterday, in what seems to be another tragic expression of Muslim-Christian tension in Egypt, one man died and several others were injured in knife attacks in Alexandria.

The direct motives or the identity of the attackers isn't yet clear, although Alexandria seems to be remaining calm, in contrast to events surrounding the DVD scandal in October 2005.