There are a couple of things evident upon arriving at the adobe-brick bus station in Siwa, hot off a nine-hour slog from Alex. The first is that the oasis — over 500km from Cairo and just 50km from Libya — is not much like anywhere else in Egypt. The second thing that is evident is that this state of affairs won’t last for long.

Siwa’s uniqueness is a product of its sheer isolation. Not even the demotic Arabic speech of Cairo, which has conquered far and wide in Egypt, is in the ascendancy here. A rough and ready Berber parlance is still more commonly heard in Siwa’s market places and alleyways, and the town’s ‘feel’ is more of the Maghreb than the Nile Valley. Such isolation bequeaths a kind of autonomy, and Siwa has always been less than enthusiastic about the rule of outsiders. In fact, the writ of the modern Arab Republic of Egypt only really fully included the oasis after a proper road was built from Marsa Matruh in the 1980s.

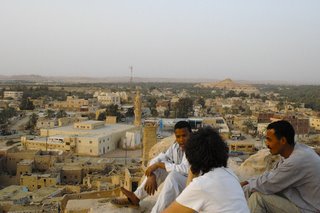

The broad plain, blanketed in date and olive groves, and surrounded by two large freshwater lakes is by any standard an exceptionally beautiful place. It supports a settlement of about 23,000 people, who are mostly involved in an agriculture which has little to do with the modern world, and who represent a culture more introverted and conservative than readily found elsewhere in Egypt.

At the centre of the settlement is a kind of arcane symbol of the oasis’ antiquity — the deserted citadel of Shali, now a crumbling, five storey relic of a harsher desert past. Even though Shali has been mostly abandoned since heavy rains in 1926, the town’s poorest, landless inhabitants still live in its dusty periphery, with teenage boys lurking at each corner to escort visitors around their precarious asset.

It is easy to see how Siwa’s possession of natural attractiveness, the relics of antiquity, and a cultural indifference to modernity make it something more than just a settlement, more than just an isolated society. In the eyes of the outside world, Siwa is a tantalising glimpse of a pristine culture, and one that is increasingly attainable. In short, it is rapidly becoming a destination.

When it comes to the raw material needed for a thriving tourist industry, Egypt has an embarrassment of riches.

Nevertheless, Siwa is a relatively untapped resource, and remains a highly valuable commodity in a market that is characterised by seemingly unstoppable growth. The Ministry of Tourism’s figures claim that Egypt welcomed 8.6m tourist arrivals in 2005 and is planning for 14m by 2011.

Such a volume of visitors, and the cash that it represents is a powerful motor for change – and arguably the sole motor for change in a place like Siwa.

Tourism, as one of its side-effects, generates infrastructure. And infrastructure generates, albeit in an indirect way, social change. Siwa’s exposure to social mores other than its own, and its political isolation were irrevocably changed with the completion of the road from Marsa Matruh. Now, it is expected that the newly refurbished airport in Siwa will begin to receive tourist charter flights, cutting out the long and daunting road trip from the north coast.

The process is fairly obvious – if you have a desirable resource in an expanding market, you exploit it. The question is how that process of ‘development’ will be managed, and by whom. In Siwa, even those that stand to gain by an influx of tourists are ambivalent about the airport. One hotelier admitted to me that Siwans are pleased to welcome a limited number, but are nervous about losing control of the process – “Of course things will be very different when they open the airport” he said, “And we will welcome the extra guests as we can. But we also know the trouble that it can bring”.

It is easy to bemoan the blight of modern tourism, voraciously devouring ‘experiences’ and ‘cultures’ at the net expense of local societies. And in Siwa there is in fact a model of sustainable touristic development, in the shape of an ‘Eco-Lodge’ on the outskirts of town. The problem however is that sustainable tourism is hardly a mass market – in fact the comfort of knowing you are exploiting nothing and no-one in Siwa comes at a hefty premium. The Adrere Amellal lodge charges about $400 a night.

If there is a model of responsible development in this respect, which could be hoped for the relatively un-developed Siwa, it is hard to find in Egypt.

In addition to the accommodation needs of foreign visitors, the middle classes of Cairo and Alexandria are fuelling a second-home construction boom that is rapidly covering the country’s coastlines with identikit holiday homes. On the road from Alexandria to Marsah Matruh, there now exists a slick of such ‘tourist villages’ that is 100km long and 2km deep from the shore. The ‘villages’, which exist behind 30ft walls are situated in stark contrast to the filthy slums of service workers and construction labourers that lie outside them on the far side of the highway. There is scant physical evidence of profit from such projects going anywhere apart from the pockets of property developers in Cairo and abroad.

If an indication is needed of the priorities of government when it comes to this kind of development, a look at the newest construction project in Siwa is pretty instructive. It is called the Mubarak Sports Village, and is as odd a monument to dictatorial paranoia as this writer has seen.

As an unwieldy reminder of the structure of power and consent in Egypt, it is perfect. The ‘village’ (in a town where household running water and electricity are by no means universal) is equipped with a stadium that looks as if it could hold at least 20,000 (Siwa pop. 23,000) and is painted bright pink. There wasn’t much sign of any sport happening within its confines.

This edifice, which so proudly announces the beneficence of the First Family is closed to the public, and has been pretty much since it was completed. It is occupied solely by wall-eyed infantry grunts who look like they wish they had never heard of Siwa. A token, if one was needed, about who holds the ear of the ruling party. A local businessman, when asked what the Sports Village was all about answered: “The Government, it has some crazy idea about what kind of country this is. This thing is ridiculous, it’s a delusion.”

So the question posed by all of this is, “Is bad development better than none at all?” Judging by recent developments, bad development is what Siwa is going to get. Is the trickledown effect of more visitors (potentially better water and sanitation facilities, and a increased cash-flow to Siwan people) worth the distortions in the local economy?

As a location somewhere between the past and modernity, and a location small enough to witness change happen ‘live’, Siwa is worth watching for the answers to these questions. Just don’t ask anyone about the local football team.

No comments:

Post a Comment