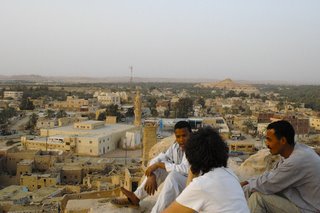

A small delegation from an organisation known as One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) visited Egypt this week, and met with various dignitaries and business leaders. Their purpose was to establish links with ICT and education professionals in the country, as Egypt is to be one of the pilot nations (along with Brazil and Thailand) in OLPC's $100-laptop scheme due to start later this year.

The basic idea of the scheme is to develop a portable personal computer for the needs of education in the developing world, manufacture it at a very low cost ($100) and sell it to governments for distribution amongst the school-age population. It sounds like a very good idea. It also directly addresses a central area of first-world angst since the internet began to 'revolutionize' our lives some ten years ago – the digital divide.

The Digital Divide is the notion that, as the individuals and economies of first-world countries make rapid advances in their co-operative ability through the internet, the developing world is left further and further behind because they do not have access to the technology. Recently, some observers have claimed that due to the availability of cheap telephony and locally manufactured hardware, certain parts of the developing world are catching up.

Whether or not that is true, OLPC is an organisation with anxiety over the digital divide at its very heart. It is the project, in part, of MIT founder and chairman Nicholas Negroponte. If the name sounds familiar, it is because he is the brother of John Negroponte, the US Director of National Intelligence and former ambassador to Iraq. OLPC is, self proclaimedly, "a new, non-profit association dedicated to research to develop a $100 laptop—a technology that could revolutionize how we educate the world's children".

Negroponte is visionary about the potential of technology to improve educational standards in places where the state fails its children. He has two basic principles –which you can read in his article in The Economist's "The World in 2006". The first is that "education is always part of the solution" - to what problem he does not specify, but we might assume he means "a lack of development". The second is that "learning, as well as coming from 'top-down' institutions also comes from exploration and independence".

It is hard to take issue with either of these pleasant banalities. What has, as yet, to be made clear is the role that the implantation of ICTs into locations where they are usually unobtainable has in encouraging either statement to become reality.

The technological side of OLPC is somewhat impressive. It is a feat of manufacturing and logistics to be able to create a functioning laptop for such little money – and the kind of feat one might expect from an eminent institution of technocracy such as MIT. The first-generation product is slated to be a Linux-based 400MhZ AMD machine, with 128Mb of SDRAM, super-low energy consumption and the ability to be cranked by hand. If you can remember the Bayliss radio, the look of the "Green Machine" as it is called, is very similar. OLPC places, naturally, a lot of emphasis on Open Source Software, although the educational content with which the machines will come equipped has not been confirmed. It is hard to find examples of quality Open Source educational software, but there are programmes which can parallel proprietary applications such as Microsoft Office and Adobe CS.

But when it comes to the interface between technology and the real world, OLPC is, unfortunately, a triumph of optimism over clear thinking.

It relies on a couple of imaginative constructions, ways of seeing the world which obscure the real conditions in developing countries, and the effects which international development produces in them. The first of these is that we, in the first world, live in a kind of techno-utopia where modernism has all but obliterated opposition to the 'rule of experts', and where our lives have been immeasurably improved by the advent of ICTs and the internet.

The second of these, which follows from the first, is that the introduction of technology into places where it is not being indigenously developed will make the lives of the recipients immeasurably better also.

The mere naming of these constructs should make the fallacy upon which so much international development is predicated obvious immediately. Common sense says that neither of these statements are necessarily true. However, a third construct is key to the OLPC project, and it is the simple belief that ICTs help learning. Now, I had thought that "Getting the Internet Helps with Your Homework" was just a particularly perfidious advertising suggestion to shift Dells and Hewlett-Packards, but it seems to have filtered its way into the development community without much critical evaluation.

Computers can, it is true, assist educational development in a constructive and supervised atmosphere. It can do so where the software, logistical support and know-how are present and affordable. But it is ridiculous to imply that ICTs can circumvent the fundamental deficits in any given national education system – which are present due to a myriad of social and economic difficulties. In Egypt, these deficits take the form of enormous class sizes, dilapidated classrooms, badly paid and under-motivated teachers, an overbearing secondary exam system and a bloated university sector. All the computer hardware in the world can do nothing about any of these. To claim that a $100 laptop can "revolutionize" education, in such an environment is well-intentioned, but foolish.

So, these are the structural difficulties that the Egypt's education system already struggles with, before it might be confronted with the difficulties of implanting large quantities of odd-looking computers. By far and away the most glaring of these secondary difficulties is literacy. Literacy is the elephant in the boardroom when international ICT corporations are doing business with the Egyptian education sector – something left unmentioned because it is too large a problem to contemplate. Granted, it is a problem that is being managed to an extent, but there is still a significant part of the female population particularly that isn't getting any schooling at all, much less being taught how to manipulate eBay.

Then we have the following headaches, in no particular order: The presence or otherwise of resources to maintain hardware, to purchase (or more likely pirate) international-standard software (why should the developing world have to muddle along with home-made Open Source programming when the first world gets the best?), the ability to train users in new applications, the ability to critically evaluate the plethora of internet sources, the money to pay for telephony or ADSL rental (dial-up in Egypt is reasonably cheap, broadband is not), the guaranteed reliability and autonomy of service providers, and the ability to take advantage of e-commerce through modern retail banking and affordable credit. It's quite a list, and it could be longer.

The above are basic requirements for an individual to be able to fully take advantage of the information age. Will OLPC provide these requirements? No. The simple reason is that the hardware itself is essentially second-tier, and is being aimed at the infrastructural level of the remote village, where electricity is at a premium (hence the hand-crank) and where the slated Wi-Max connectivity might conceivably be of use because of the absence of normal copper-wire telephony. But the ability to use such technology effectively is by no means automatically present in the places where the hardware seems destined for, and such ability is really only present at a much higher level of infrastructural development - i.e. in the lower middle classes of urban areas. A computer is something of an inappropriate addition to a household that does not have running water. The design of the OLPC project seems to rest on an odd image of the recipient as someone with a high level of basic education and fluent English, but who lives in a mud-hut in the middle of nowhere.

But who knows where the OLPC hardware will actually end up in Egypt. Despite the aspirations to sidestep 'top-down' learning, the OLPC machines will be distributed by the Egyptian government, who may have priorities other than the equitable education of its masses in mind. Now, this leads to the final point. At $100 each, the OLPC computers are to be sold at cost to, presumably either the Ministry for Education or the Ministry of ICTs. With the preliminary order reportedly one million units, this will set the purchaser back, of course, a hundred million bucks. The Minstry of Education has published its estimated spend for the five year period 2002-2007, and such a figure represents nearly 8% of its annual budget. It wasn't included, however, because OLPC was only thought-of last year.

So it is reasonable to assume that if the order does proceed this way, it will be at the expense of an increase in teachers' salaries, or much-needed infrastructural repairs. Even if the money materialises from international donors, it is still a heinous waste in the light of the country's obvious educational shortcomings, and would be money spent chasing the chimera of technological progress instead of shoring up real, traditional schools.

If the idea of OLPC seems immediately appealing, this is because in the first world we are all, almost automatically, part of the techno-utopian dream to which OLPC belongs. But the first world has all of the other resources to make use of the internet and ICTs - and the 15 million school children of Egypt mostly don't. So it might be useful to get the reading and the writing done first, and worry about the badges of techno-modernity later.